The

Sweetheart Murders

A Birthday Gift May Yield Clues About A Brutal

Double Murde

DAVIS, Calif., Jan. 27, 2007

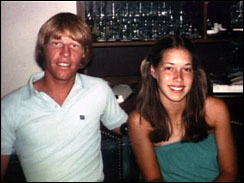

John Riggins and Sabrina Gonsalves. (CBS) |

|

(CBS) In 1980, a young couple was murdered as they were

heading to a birthday party. As correspondent Troy

Roberts reports, it would take many years, a

journalist's persistence and a clue found on a birthday

present that would bring the homicide investigation to

the next level.

More than 25 years have passed since Andrea Gonsalves

Rosenstein lost her beloved baby sister Sabrina in a

savage double murder. And not a day goes by that she

doesn’t think of her.

“We loved the beach; she loved to swim,” Andrea

remembers. “She especially loved the horses with me.

I’ve made a real effort in my life to connect her into

my life, her memory into my life, in any way that I

can.”

That connection is very much alive in Andrea’s

first-born, whom she named after her sister. Ever since

she was a small child, Sabrina Rosenstein—now 22—was

aware of her family’s loss.

“There was always a sense of something terrible that had

happened to my family that most people haven’t

experienced and can’t understand,” she explains.

In the summer of 1980, Sabrina Gonsalves was dating John

Riggins, and working for the recreation department in

the town of Davis, Calif. They were both 18, about to

start college and were in love.

John Riggins was a hometown hero, a popular high school

athlete, and the son of a prominent physician.

“I think he got a great enjoyment out of life at this

point in time. And he had all the world to look forward

to,” his father remembers.

But the two sweethearts would disappear into the thick

fog on the night of Dec. 20, 1980. Sabrina and John were

expected at Andrea’s birthday party that night, but they

never showed. By morning, with still no sign of the

couple, Andrea’s disappointment turned into fear.

“The fog would sock in Davis for days sometimes but that

night was really, really bad,” Andrea recalls. “And I

thought maybe the van went off the road. And they’re in

the field somewhere, hurt. And we have to find them.”

Police insisted they had to wait 24 hours before they

could begin searching. Besides, they said, Sabrina and

John had probably eloped.

“I was furious and said ‘No, this is completely out of

character, these are not typical 18-year-olds whatever a

typical 18-year-old is…that they would never do this,”

Andrea remembers.

That morning, the Riggins family and friends organized

their own search but police finally found the van a day

later, abandoned some 20 miles from Davis. Someone had

rummaged through it—even tearing open the gifts that

were meant for Andrea. But there was no sign of Sabrina

or John.

Hours later, the search for the couple was over—their

bodies had been hidden in the brush.

“It looked like both victims had simply been thrown into

the ditch and discarded as used garbage,” remembers Ray

Biondi, now retired, who was a detective with the

Sacramento Sheriff’s Department.

Asked what he was thinking when he saw the bodies and

how they were wrapped in duct tape, Biondi says, “We

were looking at somebody who came prepared to commit

these murders and was not afraid to get up close and

personal and kill the victims. Had absolutely no regard

for other human lives.”

There were signs that Sabrina had been sexually

assaulted. “The only obvious motive that we could even

think of was probably a sexual assault on Sabrina

Gonsalves. And then again, also, there are people who

simply kill cause they like to kill,” Biondi says.

Biondi tagged the victims’ clothing to be tested for

bodily fluids, along with another item: a blanket found

in the van, that was a birthday present for Andrea.

Biondi believes the killer was lying in wait as Sabrina

and John left her apartment on their way to Andrea’s

birthday party. The pair, Biondi says, may have been

abducted right outside the complex, as there was almost

no one around and it was very foggy that night.

The murders of John and Sabrina generated hundreds of

calls to the police, who released a composite sketch,

hoping they would find the killer before he struck

again.

With her sister’s killer still on the loose, police told

Andrea she had a special reason to be afraid. “They

said, ‘You live in the same apartment. And so, it's

possible that you were targeted instead of her.’ I

cannot express how horrifying it would be to me that it

would’ve been my fault, that I would've rather died than

have her die at any time,” Andrea says.

Sabrina’s mother Kim was also struggling to comprehend

the devastating loss. She decided that she needed to

visit the site where the bodies were found.

“It’s horrifying. Your whole job as a parent is to

protect your kids anyway. And when you can't protect ’em

you feel, you feel horrible,” she says.

As the weeks turned into months, police worked the

hundreds of leads they received. “There were a lot of

calls, a lot of leads,” Biondi remembers. “We thought we

would end up with some viable information because of the

amount of calls we were receiving on the case.”

Biondi was hopeful the crime scene would yield some

clues as well. “Inside the van there were literally

hundreds of unidentified latent fingerprints. We were

hoping that they might come up with somebody very

interesting. But as it was, we did not,” he explains.

One by one, each lead eventually went nowhere and police

were at a loss.

Six years passed, and it seemed like the case might

never be solved. But finally, a tip led police to take

another look at a similar double murder that had

happened around the same time.

“John and Sabrina were killed a month after we had

another college couple killed here in Sacramento

County,” Biondi tells Roberts.

There were many parallels between the two cases: both

involved attractive college couples who were abducted

from a public place, killed execution-style, and then

dumped around the Sacramento area.

Police did make an arrest in the other case – the

suspected killer was Gerald Gallego. But as it turns

out, on the night John and Sabrina were killed, Gallego

had the perfect alibi: he was already in jail.

Still, police were sure that there was a connection

between the murders, and they ultimately arrived at an

unusual theory: they believed John and Sabrina’s murder

was a copycat crime, staged to clear Gerald Gallego and

to suggest that the real killer was still on the loose.

Police believed the man who carried out the killings was

David Hunt, Gallego’s brother. Hunt had a long list of

felony convictions, including a kidnapping. “David Hunt

would not be beyond committing a copycat murder to take

the heat off of his brother,” Biondi says.

Police thought Hunt had received help from his wife

Suellen, and also from his frequent partner in crime,

Richard Thompson. The three became known in the press as

the “Hunt Group.” And so, in November 1989, nearly nine

years after Sabrina and John were murdered, the Hunt

Group was arrested.

There was no physical evidence in the case, so

detectives leaned on another one of David Hunt’s

partners in crime, a man named Doug Lainer.

Investigators hoped that he would turn against the

others.

“They wanted me to testify that somebody in that group

told me about these killings. That's what they wanted,”

Lainer recalls.

Lainer openly admits that back then, he was a drug

addict and a thief who would steal just about

anything—including sheets from motels, which he would

sell.

But he insisted that, despite his checkered past, he

wasn’t a killer.

Each time detectives visited him, Lainer told them same

thing. “I didn't know about these killings. I didn't

know about any of that crap. But they thought I did. So,

they could put all kinds of pressure on me and squeeze

me till I coughed it up. Well, the fact of the matter

is, I had nothing to tell,” he explains.

That’s because, Lainer says, they were all innocent.

After months of denials, Lainer was finally arrested and

charged with the murders of John and Sabrina. He and the

rest of the Hunt Group were facing the death penalty.

But on the eve of trial, a stunning piece of evidence

was uncovered. The blanket in the van, Sabrina’s gift

for Andrea, yielded a clue.

“It was determined that there was in fact a stain on the

blanket,” Biondi says.

The stain was semen that had somehow been overlooked all

this time. It was ordered tested for DNA—testing that

could make or break this case.

The DNA test of the blanket failed to match any of the

suspects. Embarrassed prosecutors had no choice but to

drop the charges against all four.

The news was devastating to Sabrina and John’s parents.

“It’s like a scab on your heart, that it breaks open and

you bleed from time to time and it never stops,”

Sabrina’s mother Kim explains.

Detective Ray Biondi was not surprised when the case

collapsed. He had always been troubled by the lack of

physical evidence. “It simply appeared to be a case of

trying to smash the square peg in the wrong hole. ‘Make

it fit; make it fit,’” he says.

Biondi had another reason to feel frustrated: there were

actually four stains on that blanket, all semen. Those

stains had only been discovered and tested for DNA some

12 years after he had sent the blanket to the county

crime lab.

“It’s one of those tear your hair out moments,” Biondi

says. “And I’m not sure about this, but the blanket was

never turned over and the semen stain was actually on

the other side.”

At that time, with no DNA databank in existence yet,

there was no way to trace the DNA to any other suspects.

So once the charges were dropped, the trail went cold.

“I even thought of suicide. I really did. I mean I

really didn’t think I could go on. But you do,”

Sabrina’s mother Kim remembers.

What the families didn’t know was that there was someone

else who had been changed by John and Sabrina’s murders:

journalist Joel Davis.

Joel, now 44, attended high school with John Riggins. In

2000, he decided to write a book about the

still-unsolved case. Joel had no way of predicting back

then that he himself would become a part of the story.

“When I was reading those court transcripts, you know,

there were times the hair on the back of my neck was

standing up because this was a fascinating case,” he

recalls.

As he kept digging, Joel realized it was not too late to

take a fresh look at the blanket. DNA technology had

become more sophisticated, and samples could now be

compared to those of convicted criminals stored in a new

database.

So in 2002, he contacted the prosecutor in charge of

Sacramento’s new cold case unit – and didn’t let up.

By that time Joel was doing his job in the face of an

overwhelming personal challenge: at the age of 38, he

was diagnosed with Parkinson’s Disease.

“I was able to get an operation that not everybody’s

able to get. A deep brain stimulation surgery that

allows me to move my hand and type and it actually

allowed me to finish this book,” Joel tells Roberts.

“I’ve had my ability to walk taken away, I’ve had my

ability to sign a check taken away but I can still

write.”

The Parkinson’s may have slowed him down a bit, but

Joel’s persistence paid off: investigators re-opened the

case.

Remarkably, within months, there was a hit from the DNA

databank.

“And they said it was one-in-240 trillion,” Joel

remembers.

It was a one-in-240-trillion match. Finally, after more

than two decades, there was a new suspect, tied to the

murders through physical evidence. And as detectives

would soon discover, this man had a very dark past.

Richard Hirschfield, a man authorities in Davis had

never even heard of, was charged in the double murder. A

convicted sex offender, his DNA was stored in the FBI

database. And authorities say it matched the DNA found

on that blanket, that birthday gift meant for Andrea.

For John Riggins’ mother, finally facing her son’s

accused killer as he was arraigned, was bittersweet and

disturbing.

“He was looking at whomever was sitting there in court….

And it was frightening,” she remembers.

Asked who this Richard Hirschfield is, Joel Davis says,

“They always said it took a pretty smart person to pull

this off. He has been described by the authorities as

‘unabomber’ smart.”

Hirschfield was also dangerous. He was convicted of a

violent sex crime some 30 years ago – five years before

John and Sabrina’s murders.

Marge and Michelle, two sisters who do not want their

last names used, were 22 and 16 years old when

Hirschfield attacked them at Marge’s apartment in

Mountain View, Calif. in 1975. It started as a robbery

at gunpoint.

Hirschfield tied them up and threatened to kill them.

When Marge told him she had no money, he went from

robber to rapist.

“It was like he was frustrated. He was mad. ‘All right

then, who wants to be raped?’ And then my sister offered

herself instead of me,” Michelle remembers.

“Anybody in my position would have done the same thing,”

Marge says. “She was my little sister, a sophomore in

high school. There was no choice.”

Hirschfield forced Michelle into a closet, while he

raped her older sister.

Hirschfield was caught four days later, lurking outside

another apartment complex in the area.

He served only five years in prison for that home

invasion and rape and was paroled in July 1980. John and

Sabrina were killed later that year.

After being paroled, Hirschfield lived with his younger

brother Joe in the town of Arbuckle, some 40 miles from

Davis. Authorities believe they were both still living

in the area at the time of John and Sabrina’s murders.

Almost twenty years later, in 1999, Joe, an auto

mechanic, married Lana.

“And he was just a really kind, gentle person – and

happy. All the time happy,” she remembers.

But Lana never met his brother Richard. “Joe didn’t talk

a whole lot about his family,” she explains. “He did

tell me that the reason he was estranged from his

family, that there was some sort of a disagreement.”

She and Joe were enjoying their new life together in

Beavercreek, Oregon. But everything changed in Nov.

2002, when detectives came knocking at their door. They

wanted to talk to Joe about his brother.

“I noticed that his face was quite red. And I asked him

if the detectives had come talk to him. And he said, yes

they had. And I asked him if that had upset him. And he

said, yes it was disturbing,” Lana remembers.

Detectives had told Joe his brother’s DNA was connected

to an unsolved double murder. Lana was completely

unprepared for what would happen just one day later: she

discovered her husband’s body in his car; he had

committed suicide by carbon monoxide poisoning.

Police seized as evidence a suicide note left by Joe, a

note that would finally help unravel the mystery of the

murders. In it, Joe expressed his love for his wife but

said he had been living with “this horror” for 20 years.

Joe then named the killer. “He said Richard did kill

those people,” Lana says. “He said, ‘I didn’t kill

anyone’ and that it would just be a matter of time until

they found his DNA there also and would be coming after

him.”

Detectives always thought that John and Sabrina’s killer

must have had help leaving the scene.

“John Riggins’ van was abandoned. So somebody had to be

around to pick him up. There’s very little likelihood

that this person would have caught a ride along the dark

highway,” says Det. Biondi.

At last, police felt they were heading in the right

direction in solving Sabrina and John’s murder.

With the arrest of 58-year-old Richard Hirschfield,

Sabrina and John’s families believe the prosecution

finally has a strong case.

Hirschfield pled not guilty. And his attorney, Linda

Parisi, insists the case is anything but a slam-dunk –

despite the DNA on the blanket, and the suicide note

from his own brother, saying “Richard did kill those

people.”

Parisi maintains that Joe Hirschfield’s suicide note is

not admissible. Whatever role he may have played in the

crime remains a mystery: Joe’s DNA was not found at the

scene. As for the DNA hit on Richard, Parisi says, “I

don’t know if we can rely on that.”

“One in 240 trillion,” Roberts remarks.

“We don’t even know what that number means,” she

replies. “Ultimately, we must have confidence in the

testing, that there was no contamination either at the

lab, or beforehand, in order to trust a result.”

But if indeed it is her client’s DNA found on that

blanket inside the abandoned van, Parisi claims someone

could have planted it there.

“Certainly there have been cases where DNA has been

planted,” she says.

Parisi claims there’s another possibility: that

Hirschfield might have been wandering in the area and

found the van.

"He had a misfortune of stumbling upon this van on the

night that Sabrina Gonsalves and John Riggins were

murdered, and somehow just left his bodily fluids on the

blanket?" Roberts asks.

"That is not beyond the realm of possibility,” she

replies.

But retired detective Ray Biondi doesn’t buy it, saying

“I find that to be totally preposterous.”

There’s someone else who doesn’t buy Hirschfield’s

innocence – his ex-wife Lynn, who was briefly married to

him 10 years ago. She is speaking out for the first time

and has a stunning accusation: that Hirschfield molested

her son.

To protect her son’s privacy, Lynn has asked 48 Hours to

not reveal her or her son’s identity. She says when he

was a child, she could not understand why her son

suddenly became withdrawn.

“When he was seven years old, he was the happiest child

you could imagine. And his eyes sparkled and he laughed

all the time. And then one day that was gone,” she tells

Roberts.

Then, to Lynn’s shock, Hirschfield was arrested for

molesting two little girls in their neighborhood.

“And I just started piecing all these little things

together. And one day I just asked him, ‘Were you

molested by Richard?’ And he said ‘Yes,’” she recalls.

Lynn never pressed charges to spare her son the ordeal

of a trial. Hirschfield denies he ever abused his

stepson. His conviction for the molestation of the two

little girls has since been overturned on technical

grounds.

This time, Hirschfield faces the death penalty, a

punishment Sabrina’s father George, says he deserves.

“Even in fact the death penalty for him would be a break

compared to what he gave the kids, when he took those

kids’ lives they didn’t get a chance to say goodbye to

their parents. And they were suffering,” George says.

But with some 100,000 pages of discovery, this case may

not go to trial for another year or two.

“Well I think the frustrating part about all of this is

whether we’ll be alive. I’m 71 years old. And that is a

concern,” says John Riggins’ mother.

Proceedings were further delayed when Hirschfield was

beaten by other inmates and suffered a broken hip. The

title of Joel Davis’ book, “Justice Waits,” seems more

apt than ever.

While Andrea waits for justice for her beloved sister,

she has filled the void in her life by adopting three

more children, always with Sabrina in mind.

“I wanted to do this. And I wanted this to be in her

memory,” Andrea tells Roberts. “I was gonna have the

kids she didn’t get to have.”

And as she thinks of that tragic, foggy night, she

derives comfort from another one of Sabrina’s birthday

gifts: a book on horses, also found in the van.

The inscription reads: “Dearest Andrea. This is just a

small token of our appreciation for all the late night

help and all the moral support and guidance you gave us

in our first quarter of college life.”

|