Jeffrey

MacDonald: A Time For Truth

Imprisoned Former Green Beret Doctor Says He Has

New Evidence To Prove He Did Not Kill His Family

(Page 1 of 8)March 17, 2007

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

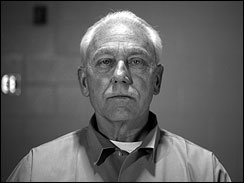

Dr. Jeffrey MacDonald (Josh Gelman)

|

|

(CBS) Three times a week,

a woman named Kathryn MacDonald makes the 140 mile drive

from her home outside of Washington DC, to visit an

inmate at the Cumberland Federal Prison in western

Maryland.

As correspondent Bill Lagattuta reports, Kathryn is the

newest woman in Jeffrey MacDonald's life. They were

married in 2002, in prison, some 23 years after

MacDonald was found guilty of the murders of his first

wife and 2 children.

Kathryn makes her living running a small school for

aspiring young actors, but she has another job as well:

she’s caretaker of the life Jeffrey MacDonald left

behind. Her garage is filled with Jeffrey's belongings –

memories that span back decades.

She was instantly fascinated when she first read

MacDonald’s story. The more she read, the more convinced

she was of his innocence. Eventually she decided to

write him in prison.

"We just became very close very quickly. And she began

visiting. And we began, you know, looking back into the

past and looking forward into the future," MacDonald

tells Lagattuta.

It's a future which, because of federal prison rules,

has yet to include a honeymoon.

"People are fascinated, I think, by women who reach out

to men in prison. Is there something about you that had

you go that direction in your life?" Lagattuta asks

Kathryn.

"No," she says. "I think it's something about him. And

that's that he doesn't belong there. He's innocent."

Innocent or guilty, 27 years in prison is an incredible

waste for someone whose future was as bright as Jeffery

MacDonald’s. He made his mark early on, in high school,

where he was voted "most likely to succeed." From there

he went on to Princeton University, and Northwestern

Medical School, and then, at the age of 25, he got a

captain's commission as a doctor in the Army’s elite

Green Berets.

Along the way, MacDonald managed to capture the heart of

his high school girlfriend, Colette Stevenson. They were

married while he was still in college at Princeton.

Over the next seven years, as their family grew, it

appears that the MacDonald's were well on their way to a

seemingly perfect life.

But in America, things were far from perfect. The year

was 1970.

"This was an era of shock and counterculture rage in

America," explains Bernard Segal, who at the time was

MacDonald's defense attorney and now is a law school

professor in San Francisco. "I was a lawyer for people

who felt they were not represented by the system and who

were outside the system."

But in 1970, Jeffrey MacDonald, was, in fact, deep

inside the system. Jeffrey, Colette and their daughters

Kimberly, age five, and Kristin, age two, were stationed

at Ft. Bragg, in Fayetteville, North Carolina.

Based on home movies taken on Christmas morning, it’s

easy to believe that the MacDonald family didn’t seem to

have a care in the world. But some two months later, at

3:33 a.m. on Feb. 17, 1970, all of that changed forever.

What happened in the MacDonald house that night is one

of America’s most enduring murder mysteries – the

subject of a best-selling book, a sensational TV movie,

a mystery story kept alive by its charismatic leading

man, Dr. Jeffrey MacDonald.

On the morning of Feb. 17, 1970, Army MPs responded to a

call for help at the MacDonald residence. They found the

couple's children dead in their bedrooms; Capt.

MacDonald, wounded and unconscious, lay on the floor,

beside the body of his dead wife.

MacDonald, still

alive, was rushed to the hospital. "They finally

brought in a doctor who I knew on the staff. And

he is the one, I believe, who told me that

Colette, Kim, and Chris were dead. And you can't

accept something like that. It doesn't make any

sense," he recalls.

In fact, that morning MacDonald wasn’t the only

one having trouble making sense of what

happened. |

|

Bill Ivory was in charge

of the investigation to determine exactly what did

happen to the MacDonald family. "I was a CID agent,

which is a criminal investigator for the Department of

the Army," he explains. "We sent agents to interview him

at the hospital…they had been told that he had been

attacked by some hippies."

It’s a story that MacDonald has not wavered from in 37

years. Asked what he remembers of the people he says

attacked him and his family, MacDonald says, "I saw four

people. I saw two white males and one black male, as

they were assaulting me. One glimpse I saw what looked

like a blonde female and she had a floppy hat on. And

there was a light under her face. To this day, I don't

know if she was holding a candle, or it was a light."

"I heard a female voice say, 'Acid is groovy, kill the

pigs.' I heard that several times," MacDonald recalls.

"There became a moment in time where all I was doing was

fending off blows with both my hands wrapped up in my

pajama to."

Suddenly, MacDonald says he felt a chest pain. "Jeff

MacDonald was stabbed right in the center of his chest

with an ice pick, puncturing his skin, puncturing the

layers below," explains his lawyer, Bernard Segal.

But the attack on his family was considerably more

vicious as revealed by their autopsies. Colette suffered

two broken arms, a fractured skull and was stabbed more

than 30 times. Five-year-old Kimberly's skull, jaw and

nose were badly broken and her throat was severely cut.

And Kristen, just two and a half, was stabbed repeatedly

in her chest and back. The autopsy also revealed one

last devastating detail: Colette was five and half

months pregnant with a son.

That’s MacDonald’s version of what happened that night

and he tells a very compelling story and his new wife

Kathryn agrees. "He's not a criminal. If I thought

otherwise, I wouldn't be involved at all. And much less

devote my entire life," she explains.

And with that kind of support, MacDonald did something

he swore he would never do: in 2005, he applied for

parole. "It's possible they might consider the full

record of my conduct, my behavior, my personality, how

I've carried myself through 25 years of imprisonment,

look at that in conjunction with my record as a

civilian," he says.

But there are others who feel that MacDonald is right

where he belongs. For one, former CID agent Bill Ivory

says he's "not buying it."

It has been more than three decades since Ivory first

set foot inside the home of Jeffery MacDonald. But the

memories of that morning are still fresh.

"On the headboard of the bed, the word pig was written

in blood," he recalls.

MacDonald had told investigators that these brutal

murders were committed by hippies, who had broken into

his house – a story that in today’s world, seems a

little tough to swallow.

Peter Kearns, an Army investigator from Washington DC,

led a follow-up investigation into the MacDonald case,

which included producing and starring in a filmed

presentation of the evidence.

MacDonald tells Lagattuta he believes the perpetrator

was someone he had turned in for illegal drug use.

But the more closely investigators examined the

apartment, the more closely they began to question

MacDonald’s claims. "The coffee table was laying on its

side but other than that there was no sign of any

monumental struggle with him and three or four other

people," Ivory remembers.

Crime scene investigators will tell you that the real

truth is always found in the evidence, and the evidence

that Bill Ivory and his team found in the apartment,

they say, tells a story very different than MacDonald’s

– a story that points not to a group of hippies but to

an enraged husband.

"The theory that we come up with was that there was an

argument. Something started in the master bedroom. He

may have hit her first or she may have hit him first,"

Ivory tells Lagattuta.

A dull kitchen knife was found near Colette’s body but

this was not what was used to kill the MacDonald family.

It was out there, through the back door, that

investigators found what they believe were the three

murder weapons: an ice pick, a paring knife and a

31-inch length of building lumber, which investigators

believed was at one time part of a slat of Kimberly's

bed.

"We believe also the older girl was in the bedroom with

them and got in the middle of the fight between them,"

Ivory explains. "He swatted back and hit her on the side

of the head and dropped her to the floor."

Because each member of the MacDonald family had a

different blood type, investigators were able to follow

the blood evidence like a trail of breadcrumbs left by

the victims. "He went and took the bedding off of that

bed in the master bedroom and believe he wrapped the

older girl in that, getting blood on him from her and

getting her blood on that sheet," Ivory explains.

The trail led them from the master bedroom to Kimberly’s

bedroom, here, where investigators say MacDonald placed

his daughter's body back in her own bed.

"While he's doing that, his wife regains consciousness

and goes to the baby's room and lays across her on the

bed, obviously in an attempt to protect her," Peter

Kearns explains.

Ivory says MacDonald followed her into that room. "And

he began beating her more there with the club. That's

evidence by blood sprays that were on the wall and on

the ceiling."

What the investigators say happened next is what truly

makes MacDonald a monster in their eyes: they say after

he killed his wife Colette and his daughter Kimberly, he

came back and stood to face his youngest daughter

Kristen, who was still in her bed.

"And then he killed her. And the only reason in the

world that he killed her was because she was a witness.

And she was old enough, she could say, 'I saw daddy

hitting mommy,'" Ivory argues.

It's at this point they say, with his entire family now

dead, in order to be believed, MacDonald decided he had

no choice but to include himself in the attack.

Now a victim himself, investigators say MacDonald then

went about setting a stage to fit his story of an attack

by drug-crazed hippies, a story they discovered

MacDonald may have borrowed from some very recent

history.

In the summer of 1969, just six months earlier, the

nation was stunned by a seemingly senseless series of

homicides in southern California – crimes carried out by

the cult-like followers of Charles Manson. An issue of

Esquire magazine, found in the MacDonald home, contained

a detailed account of the murders.

"It described the crime scenes, described the word pig

being written on the walls, described the hippies coming

in and just having mayhem in the house," Ivory tells

Lagattuta.

Investigators also found a finger smudge, in blood,

along the edge of the magazine. While it could not be

positively linked to MacDonald, it worked with Ivory's

theory of the crime.

Bill Ivory and his team’s interpretation of the evidence

pointed them to just one suspect: Jeffrey MacDonald, who

was charged by the Army with the murders of his pregnant

wife and their two young daughters.

But, says MacDonald, "I was in the house that night. I

know what happened. To me, it was inconceivable that

anyone, anyone could buy this hypothetical scenario."

In fact, MacDonald was right. After a three-month

military hearing, the Army’s official position was that,

despite the significant efforts of their own

investigators, there was not enough evidence to court

marshal Jeffrey MacDonald.

Bill Ivory says he was shocked. "Because I knew that

there was enough evidence to put reasonable suspicion in

anybody's mind that perhaps this guy had done that."

Jeffrey MacDonald thought his ordeal was over and

shortly thereafter received an honorable discharge.

While the Army seemed to be done with MacDonald, the

investigators still had no doubt as to who committed

these crimes. But until they could prove it in a court

of law, Jeffrey MacDonald would remain a free man.

"When I first came to represent Doctor MacDonald, I

wondered to myself, is it possible that he murdered his

family?” remembers MacDonald's defense attorney, Bernard

Segal.

It’s the one question that has always haunted this case

and every one involved in it: was MacDonald capable of

these brutal murders?

Segal defended MacDonald when the Army tried and failed

to indict him due to a lack of evidence. "He was now a

man who had no family and who wanted to try and start

his life over again," Segal remembers.

And MacDonald did just that: like a lot of young single

men at the time, he headed west, to Southern California.

MacDonald found a new career in emergency room medicine,

and a new lifestyle which included all the spoils of

success.

With the Army’s case dropped and civilian authorities

not particularly interested in prosecuting, MacDonald

might simply have faded from public view. But he

couldn’t seem to let it go. Apparently enjoying his

new-found celebrity, MacDonald continued to try his own

case in the court of public opinion.

On Dec. 15th, 1970, MacDonald appeared on the popular

late-night program "The Dick Cavett Show," where it

became very clear that MacDonald was fast becoming his

own worst enemy.

"My wife came home and we had a before-bedtime drink

really and watched the beginning of a late-night talk

show," MacDonald told the audience.

Dick Cavett remembers well the night he was face to face

with MacDonald. "His affect is wrong, totally wrong. My

affect was, 'Gee, to find your wife and kids murdered.'

And even his answer to that was somethin' like, 'Hey,

yeah, isn't that somethin'?' Almost sounded like Bob

Hope. Very like Bob Hope," Cavett remembers.

Watching the show that night, Colette's family was

extremely disturbed by MacDonald’s appearance. "All he

spoke about was how his rights had been violated. I

don't think he once mentioned about 'Let's get the

murderers. My family's been killed.' But I remember him

grinning like a Cheshire cat," recalls Colette’s older

brother, Robert Stevenson.

Colette's stepfather, Freddy Kassab, who had at first

sided with MacDonald in his defense, was so incensed at

his son-in-law’s behavior that it became the seed of an

obsession to bring him to justice.

"He sat around a table that I still have at home where

you can see the elbow marks as he smoked pack after pack

of cigarettes, trying to decide how this happened,

drawing the diagrams, plotting it with the X's where the

bodies were, the differing blood types," remembers

Colette's brother Robert.

Realizing the government had no plans to indict

MacDonald, Kassab joined forces with Army investigator

Peter Kearns, and together they took matters into their

own hands.

"It wasn't until Freddie and I went from New York down

to Clinton, North Carolina to swear out a citizen's

arrest. That's when the federal government got off their

duffs and got an indictment and a grand jury," Kearns

remembers,

On Jan. 24, 1975, Jeffery MacDonald was arrested once

again, this time by the federal government.

Wade Smith, one of the top trial lawyers in North

Carolina, was chosen to partner with Bernie Segal. Their

defense strategy was a simple one. "Is it possible for a

person to live a good life and all of a sudden, in one

moment, slaughter and mutilate his children, stab his

wife many, many times, and then live out his life and

have nothing like that happen again? And it suggests to

me a reasonable doubt about whether he did it in the

first place," Smith says.

When his trial finally began on July 16th, 1979,

MacDonald had little doubt what the outcome would be: he

told reporters he'd be found "not guilty."

During the next six and a half weeks, 60 witnesses

testified, hundreds of items were placed into evidence,

and three verdicts were read: guilty.

MacDonald says he "couldn't believe it."

Almost a decade after the murders of his family, the

government was satisfied that justice was finally

served.

"The sentence and the decision of the jury…we’ve feel

vindicates us completely," Freddie Kassab said of the

verdict.

Former federal Assistant District Attorney Jim Blackburn

is still asked to talk about the most important trial of

his career. "And the Justice Department thinks we’re

probably going to lose the case that’s why they’ve asked

me to ask you," he recalls.

What made him think he could win this case, when the

military said MacDonald was innocent?

"We didn't think we would win this case. I thought it

would be almost impossible," Blackburn admits.

But Blackburn and his co-consul Brian Murtagh achieved

the impossible, convincing the jury that there was no

one in that apartment that morning except Jeff

MacDonald.

And since all the evidence was found in the MacDonald

home, the prosecution brought the jury to the crime

scene, which nine years later, remained untouched, to

see for themselves.

"The strength of our case always was very simple. The

physical evidence, the scientific evidence, his

statements. That was our case," Blackburn recalls.

It was a considerable amount of information that seemed

to be overwhelming the jury. Then the prosecution did

something with a piece of evidence which made every

juror sit up and take notice. It had to do with a pajama

top that MacDonald was wearing that night.

Remember, MacDonald says he was asleep on the couch when

he was attacked. During the struggle, he says, the

pajama top was pulled over his head and that it somehow

became entangled in his hands and that he held it up to

fend off the deadly blows of the ice pick. But the

prosecution maintained all along that the pajama top

itself told a very different tale.

Blackburn says if MacDonald had told the truth, not only

would he be dead, the pajama top would be shredded.

Blackburn and Murtagh explained to the jury this was

clear proof that MacDonald’s story was a lie and that in

fact, he covered his wife’s body with the top and then

repeatedly stabbed her through it with the ice pick.

For defense attorneys Bernie Segal and Wade Smith, time

has done little to ease the frustrations they

encountered trying to defend MacDonald, even with

something as basic as a request to examine the evidence.

"The government's response is 'Doctor MacDonald is not

entitled to receive this evidence now because he didn't

ask for it in time.' O didn't know whether to cry or to

laugh," Segal says.

But Blackburn shrugs off accusations the government

wasn't playing fair. "Well, they lost. That's sour

grapes. They just lost."

Equally frustrating was what MacDonald’s team discovered

when they focused on the investigation of the crime

scene itself, which they still consider a model of

incompetence.

"Twenty-seven different people marched through the crime

scene," Segal explains. "Destroying a great deal of what

was potential evidence there without a doubt."

But Blackburn says the crime scene wasn't destroyed or

bungled. But he does acknowledge it was done perfectly.

Regardless of the condition of the crime scene, the

defense believed they had something that would clear

MacDonald once and for all: an eyewitness to the

murders, the mysterious blond woman in the floppy hat.

Her name was Helena Stoeckely, the daughter of a retired

Fort Bragg colonel and an unlikely savior for Jeff

MacDonald. Just 18 at the time of the MacDonald murders,

Stoeckley lived at the center of the Fayetteville drug

community.

Her story was astonishing. She believed she was actually

in the MacDonald house that night with a group of

friends, all drug users, who killed the MacDonalds.

In fact, an MP, Ken Mica, testified that while

responding to MacDonald's call for help, he saw someone

fitting Stoeckley’s description standing on a corner not

far from the MacDonald residence.

"Our dream was that after five weeks in this trial

Helena would come, Helena would at last tell the story,

and she would tell it to a jury," Wade Smith recalls.

But that’s not what happened when she was called to the

stand by the defense. "Her basic testimony was she

didn't know where she was that night," Blackburn

explains.

"Just a four hour gap between midnight and 4 a.m., she

claimed to have a lapse of memory. It's absurd," says

Segal.

Asked if Stoeckley lied on the stand, Segal says, "She

lied about whether she remembered what was going on but

she lied out of a defensive need to protect herself. She

knew the government was looking at her."

Following the trial, Ted Gunderson, former chief of the

Los Angeles FBI office was hired by MacDonald’s team to

search for any evidence which could be used for an

appeal.

Gunderson eventually convinced Stoeckley to go on the

record, which she did in 1982, appearing on 60 Minutes.

When she told her story, Gunderson says he believed her.

"Because she said that she tried to ride the rocking

horse in the small bedroom … and she tried to get on it

and she couldn't because the spring was broken."

Asked why that would be significant, Gunderson says,

"Because the only people that knew that spring was

broken on the rocking horse was the family, the

MacDonald family."

But 1970 crime scene photos, recently obtained by 48

Hours from the Department of Justice, seem to show that

none of the springs on the toy horse were broken. Once

again the courts chose not to believe Helena Stoeckley

and MacDonald’s early appeals were denied.

In 1983, at the age of 32, Stoeckley died of cirrhosis

of the liver, but the question of her involvement in the

MacDonald murders is still very much alive.

"The bottom line is Helena Stoeckley and some friends of

hers, came into my house that night and murdered my

family and left me unconscious," MacDonald insists.

How does he know it was Stoeckley and her friends?

"Because they said so. Because I saw them there. Because

there is evidence tying them to the crime scene,"

MacDonald says.

It's evidence the defense didn’t even know existed,

evidence that would give MacDonald one more chance for

freedom.

MacDonald has desperately held on to the goal of proving

his innocence since 1979. But with a new wife and a new

life waiting for him on the outside, MacDonald is

knocking on a different door to freedom: parole.

"I would never go before the parole board if it required

any sort of admission of guilt. They have assured me

that is not the case," MacDonald says.

"He's not gonna admit remorse for something he didn't

do. I think it'd be fair to say he's sorry that he

couldn't save his family. I know he feels that way. But

what's changed that he's thinking of me. That I'm out

here waiting," his wife Kathryn adds.

Tim Junkin and his partner John Moffett are the latest

in a long line of lawyers who’ve been enlisted, without

pay, to continue MacDonald’s fight.

In the years following the trial, using the Freedom of

Information Act, new evidence was discovered in the

government files that had never seen the light of day.

"There was wax found in places in the apartment that

didn't match any of the candles found in the MacDonald

apartment," Junkin points out. "There was skin under the

fingernail of Colette MacDonald that was not turned over

to the defense."

"Black wool fiber found on the bloody murder weapon,

which the government, despite all it’s efforts, couldn't

match to any fabrics in the MacDonald apartment," he

continues.

And one piece of evidence in particular, seemed to be

the needle in the haystack MacDonald had been

desperately searching for. "There was a blonde, 22-inch

wig hair, or wig hairs found at the scene, that the

defense attorneys were never told about," Junkin

explains.

It's a synthetic hair they say is too long to match any

of the children’s dolls in the house and therefore could

only have come from a wig. Was it Helena Stoeckley's

wig?

More appeals were filed based on this new-found

information. In fact, MacDonald’s case has been appealed

to the United States Supreme Court more than any other

in history. But as far as the government was concerned,

one hair and a few fibers were not enough to get

MacDonald a new trial.

In May, 2005, with his appeals exhausted, Jeffrey

MacDonald, with his wife by his side, finally met with

the parole board.

"I was seated at the end of this long table. I got to

look straight and direct at him and at his wife,"

remembers Robert Stevenson, who represented his sister’s

family at the hearing.

"I said to him, 'My joy in you, Mr. Macdonald, is that

you are the complete sociopath that you are. And that

you're never going to admit what you did. And that I'm

going to have the pleasure of knowing that you're going

to stay here and rot in jail for the rest of your

life.'"

Also at the hearing, a voice was heard Jeffrey MacDonald

probably assumed he would never hear again: Freddie

Kassab.

"In 1989, Fred Kassab, my stepfather had made a tape

knowing that he was in ill health and might not survive

too long," Stevenson explains.

"I want to be sure he serves out his sentence the way it

should be served out. I don’t want him walking around

the streets," Kassab could be heard in the 1989

recording.

Once again, Kassab’s efforts would help keep MacDonald

behind bars. The board’s official decision: parole

denied.

But Jeffrey MacDonald is not beaten yet, and maybe never

will be. Last winter, a federal court of appeals granted

a motion filed by MacDonald’s attorneys to present new

evidence to the court, including testimony from retired

U.S. Marshal Jim Brit, who claims that Helena Stoeckley

admitted to him and the prosecutors that she was

involved in the murder of MacDonald’s family.

"He heard Helena Stoekley tell Jim Blackburn that she

had been inside the MacDonald apartment, that they were

there to acquire drugs and then specifically and

emphatically remembers Jim Blackburn saying to her, 'If

you testify to the things that you've just told me, I

will indict you for first degree murder,'" Junkin says.

But Blackburn says Stoeckley was never threatened with

prosecution if she were to tell jurors she had been in

the MacDonald home.

"If the court accepts the testimony of Marshal Brit as

true, then James Blackburn committed a fraud on the

court and elicited perjured testimony in front of the

jury of this witness.”

It's a stunning accusation and MacDonald's lawyers

charge that Blackburn's own history gives it

credibility. In 1993, Blackburn, working as a defense

attorney, pled guilty to charges unrelated to the

MacDonald case – charges of embezzlement and fraud. He

resigned his law license and served three months in

state prison.

"So if the system works correctly, all of this evidence

taken together, I think, should entitle Jeff MacDonald

to a new trial," Junkin argues.

"We're at a point in this case now where I think it's a,

there's a legitimate possibility that I will be winning

this case. And I think that I, there will be a time in

the hopefully fairly near future where I can begin

really rebuilding a life with Kathryn," MacDonald tells

Lagattuta.

"I know that he'll be back and he'll be back. That's why

when someone said to me the other day, 'Will this ever

end?' Sure, it'll end for me when I'm dead or he's

dead," comments Colette's brother Robert.

MacDonald is confident he will one day leave prison.

"Oh, I'm sure of that. I'm positive of that. I've never

wavered on that. I've had bad days, bleak moments. But

I'm sure of that."

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Jeffrey MacDonald will be eligible to reapply for parole

in the year 2020. He will be 76 years old.

|